“A new kind of magazine for a new kind of woman.” This is the tagline with which one of the UK’s largest publishing companies, George Newnes, introduced Nova to the newsstands in 1965. In the midst of the sexual revolution, Nova stood out from other glossies because it talked about women’s issues as they had rarely been addressed before in other mainstream titles. For a decade, the popular monthly covered issues such as contraception, abortion, women’s precarity after divorce, gender pay gaps, and the sexualization of childhood. Nova not only stood apart from other women’s magazines of the time because it addressed feminist issues, but also because its covers—especially from the year 1969 onwards—were sexy. Extremely so. The kind of sexy that reminds you of Playboy magazine, which appeared twelve years earlier than Nova with the straightforward tagline: “Entertainment for men.”

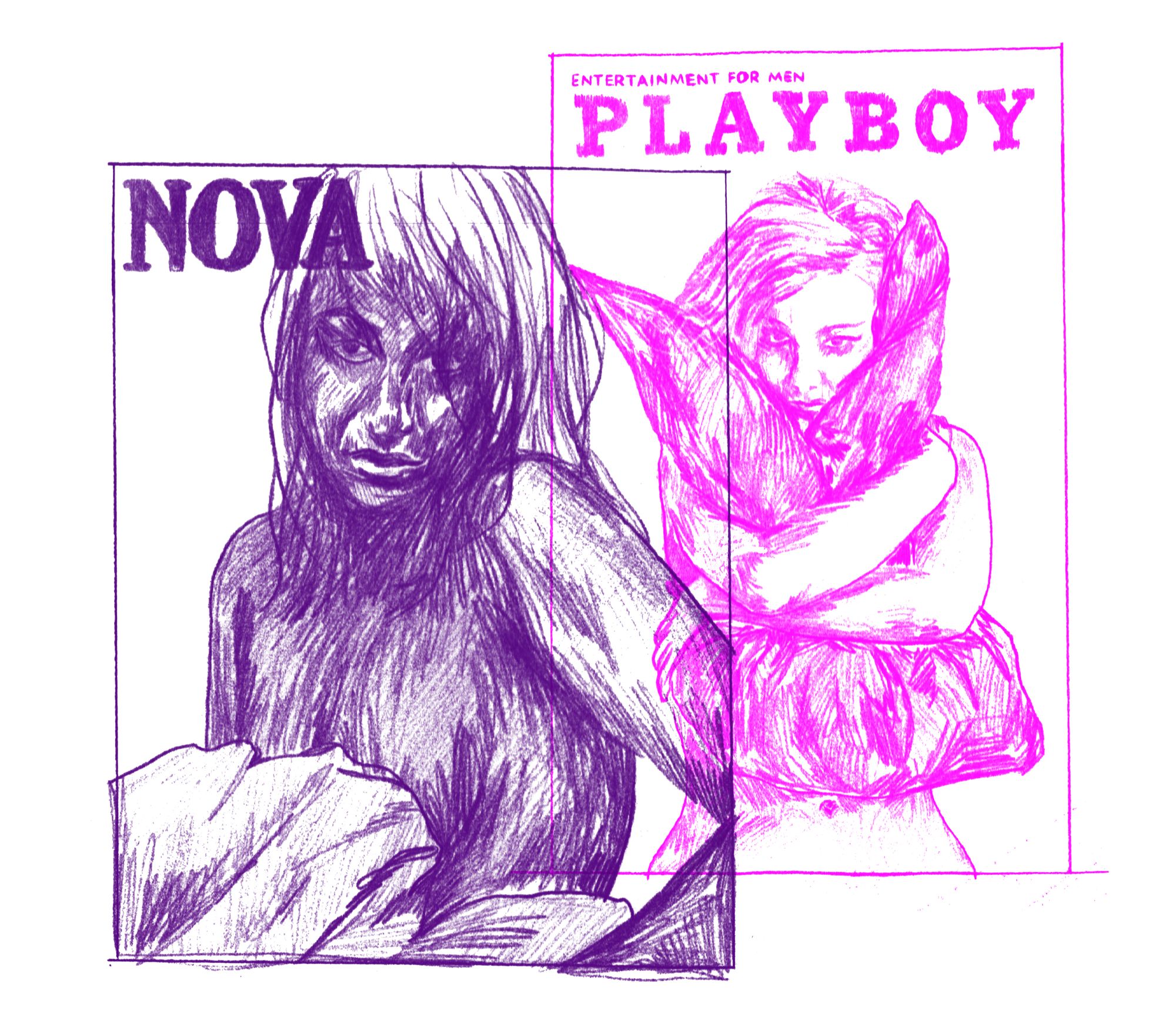

When Nova was created in the 60s, George Newnes exclusively hired men to direct it. Its first woman editor, Gillian Brooke, was appointed about six years after its first issue, in December 1970. Until then, Nova’s identity had been shaped mostly by men, with the covers taking a highly sexualized turn once David Hillman

became art director in June 1969.

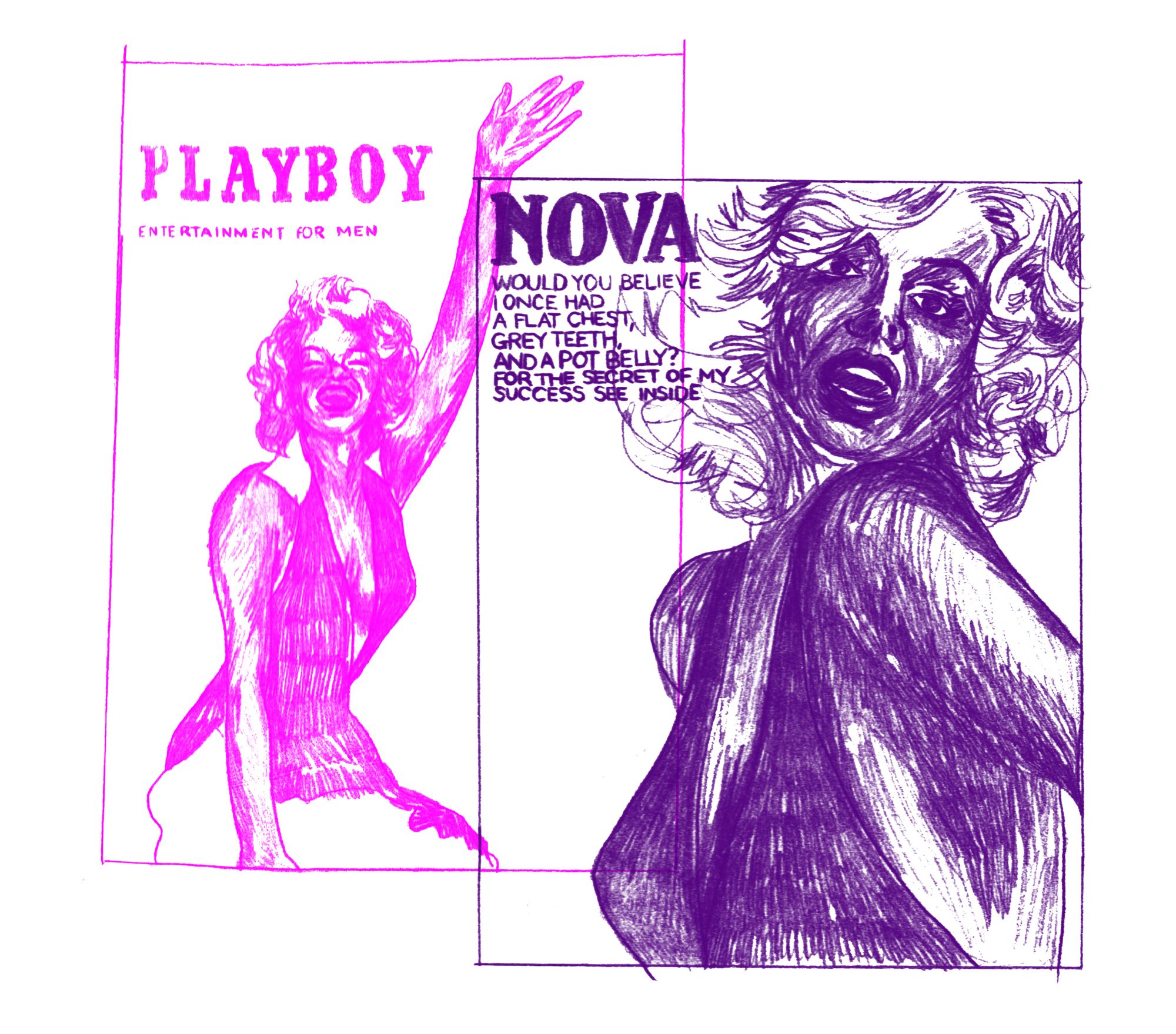

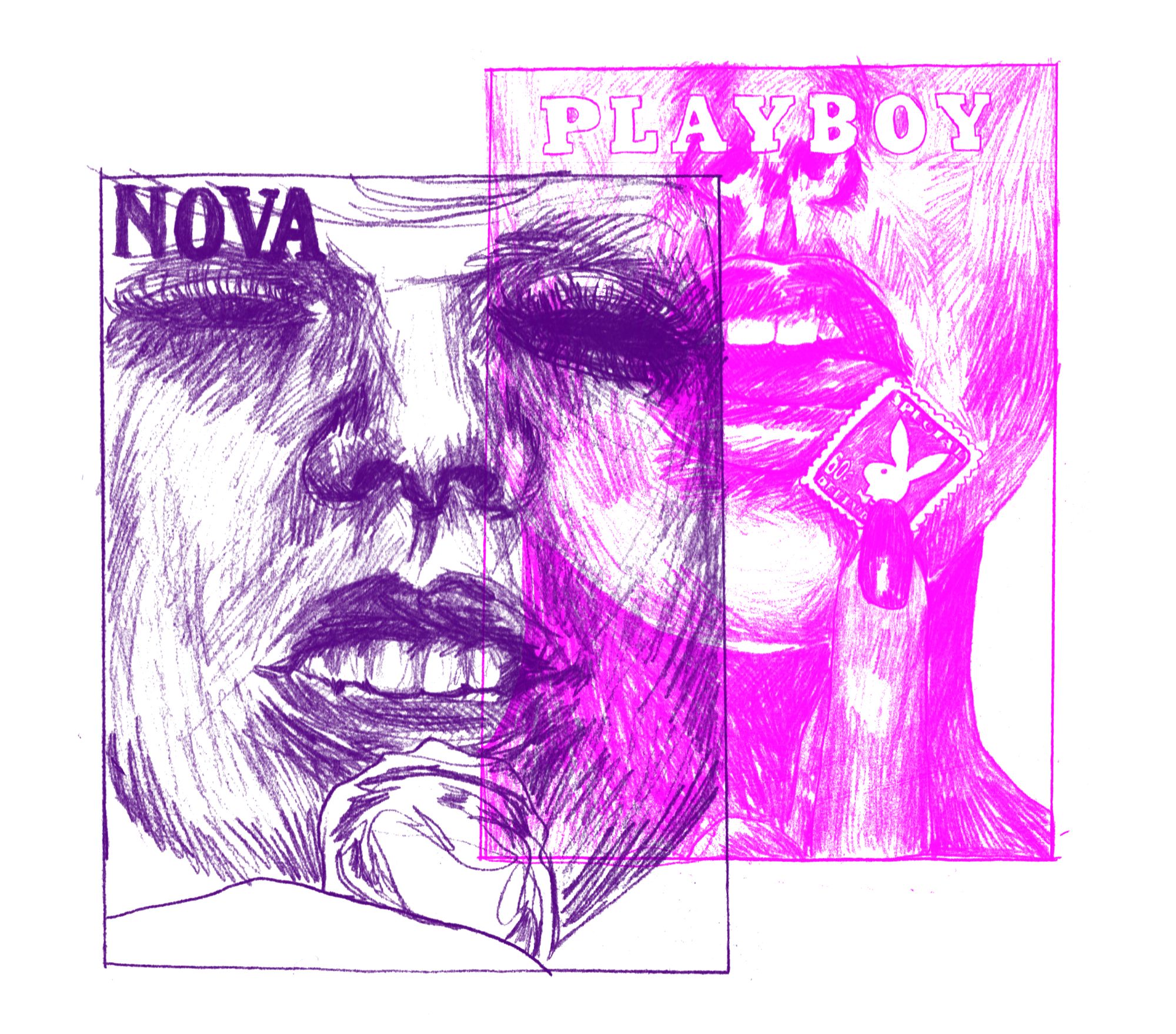

The cover of the August 1970 issue is emblematic of Hillman’s approach: A blonde model appears on the front, dressed as and posing in the style of Marylin Monroe (who incidentally featured on the very first cover of Playboy in 1953). She is accompanied by the gripping headline: “Would you believe I once had a flat chest, grey teeth, and a pot belly? For the secret of my success see inside.” This tagline questions the image of women in the media with satire and irony. But there is an ambiguity at play, one referred to by former contributor Yvonne Robert as a deliberate strategy to attract an audience that was wider than, say, feminist publications like the UK’s Spare Rib, which mostly targeted women. The trick: Consumers first notice the Playboy-look-alike cover, and only on a closer look do they notice Nova’s satirical headline.

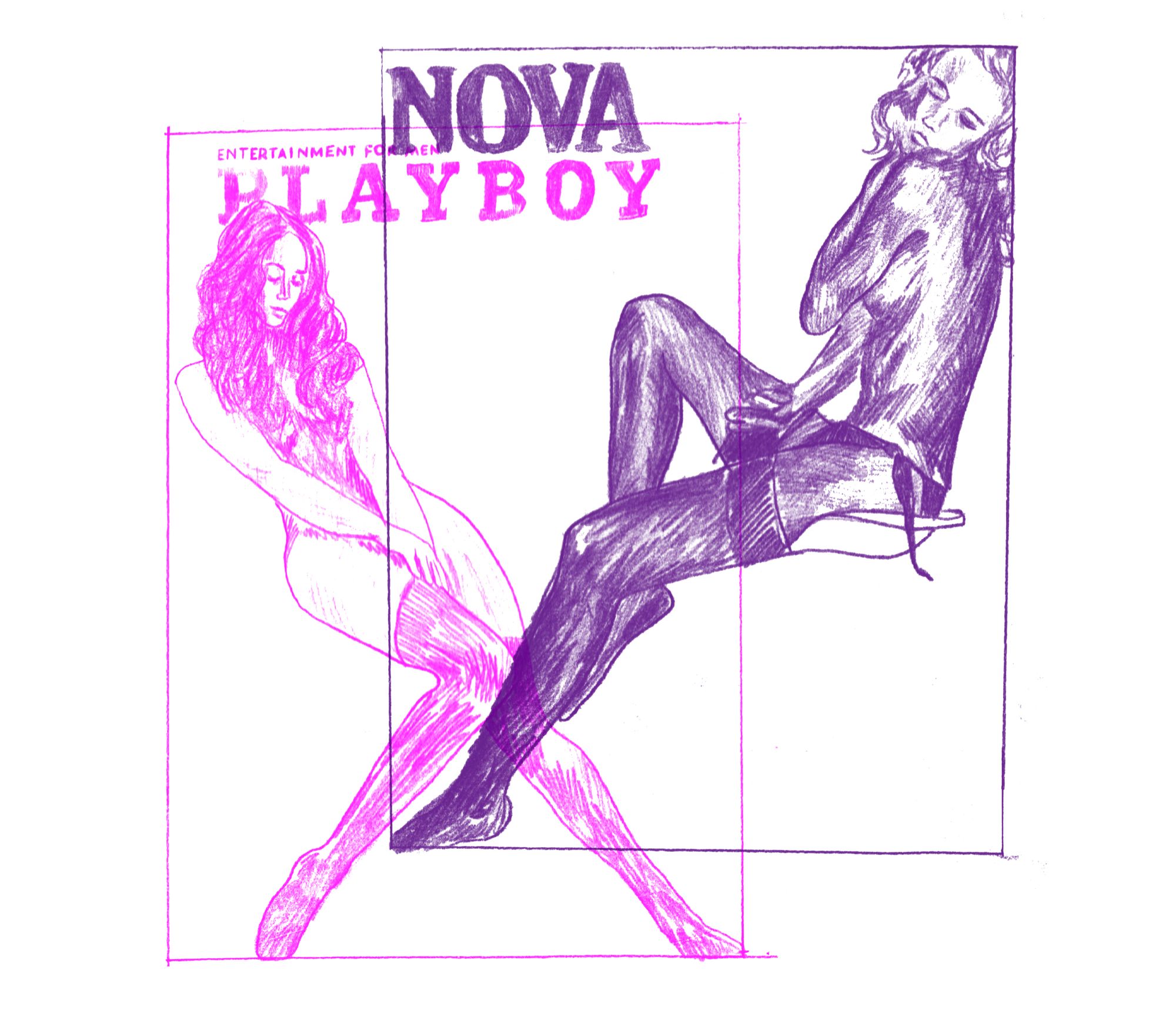

This strategy raises the question: Who ultimately benefited from Nova looking like Playboy? And how did Nova contribute to women’s emancipation as a publishing product, when it was adorned with Playboy-look-alike figures? In hiring few women in leadership positions on the magazine, and in touting those very same cover design tricks as chauvinistic glossies, it seems George Newnes didn’t really create Nova to contribute to the women’s movement but rather to capitalize on it.

In the late 60s, George Newnes was run mostly by men. It was a corporation that relied on advertizing revenue. Reading between the lines, one could say that the “new kind of woman” that these men addressed in the tagline of Nova were, actually, nothing more than a newly discovered market potential. One could also say that Nova embodied the perfect emancipated woman to the eyes of the men that invested in its publication: a woman who takes part in the sexual revolution but still aligns with the stereotypical traits enjoyed by the heterosexual male gaze.

In her recent thesis on the magazine’s history, fashion historian Alice Beard found that men made up about a third of Nova’s readership. With its glossy covers, George Newnes publishing could reach a wide market that included both the emancipated woman and the Playboy enthusiast. The ambiguity of its covers—is it satire, or is it sexy?— indeed, seems a deliberate strategy. Nova’s “new kind of woman” could moonlight as “entertainment for men.”

Floriane Fo Misslin (they/them) is a researcher and design educator. They are a lecturer at London College of Communication and a doctoral researcher in Visual Sociology at Goldsmiths University of London in the UK, and a tutor at Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands. Fo’s research examines how representations of gender nonconformity and queer sexualities are negotiated in processes of fashion production. Working with professionals and students in the creative industries, they develop participatory and visual research methods expanding the use of mood boards and diagrams.

This text was produced as part of the L.i.P. workshop, and has previously been published in the Feminist Findings zine.